Noël Hallemans

University of Oxford

Date: January 21, 2026

Time: 1000–1100h ET

The Electrochemical Society hosted “Physics-based battery model parametrization from impedance data,” a live webinar by Noël Hallemans (University of Oxford), on January 21, 2026. A live Question and Answer session followed. Answers to some of the questions not addressed during the broadcast follow.

Replay Webinar

Q&A

You showed EIS data all the way down to 0.4 or 0.2 mHz. How important is this extremely low frequency data in parametrizing the model? How good is the parameter fidelity when only using data to 100 mHz for example?

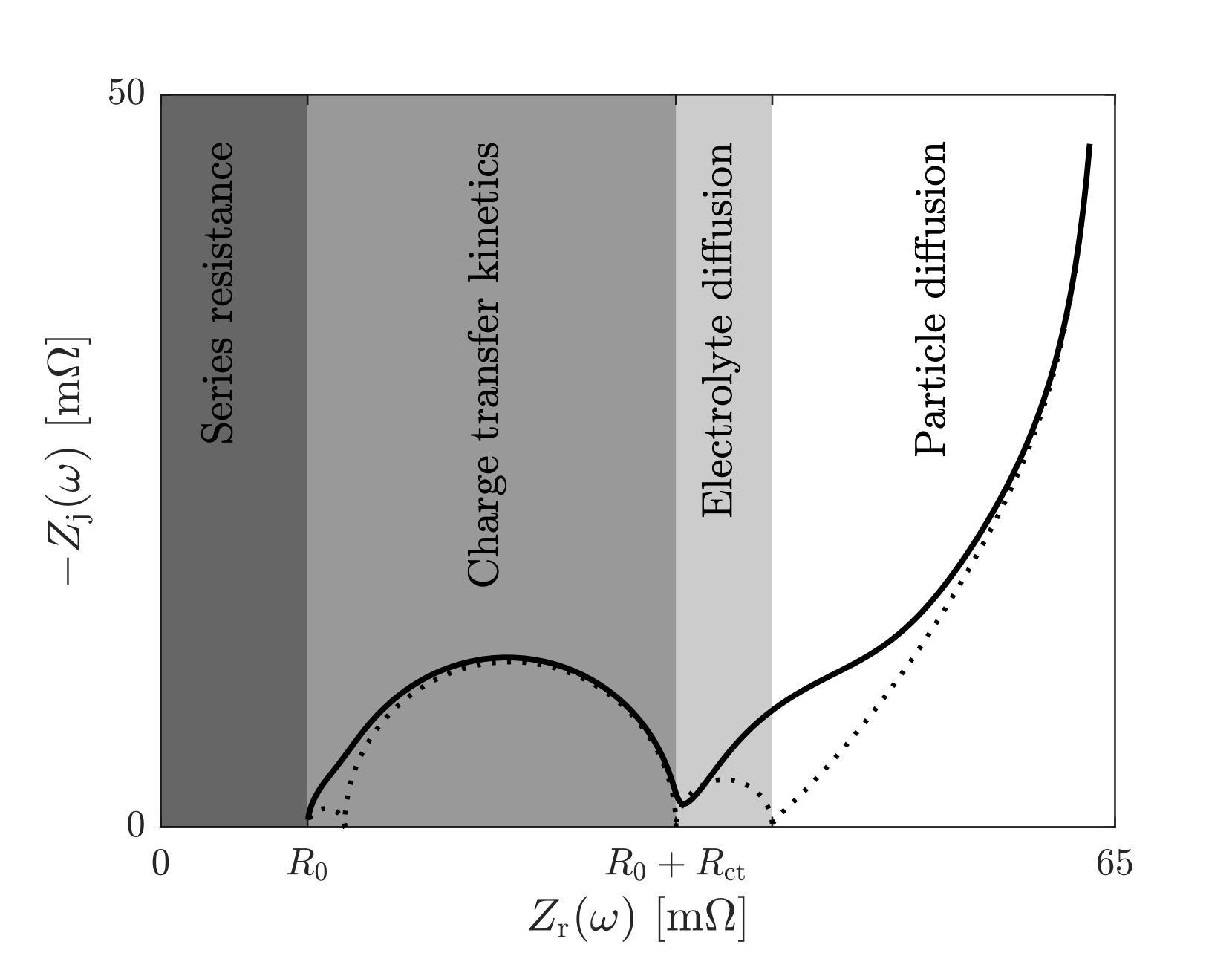

The measured impedance data does indeed go as low as 0.4 mHz, which requires long experimental times. The motivation for including such low frequencies is to capture lithium diffusion behavior in the particles. Information about the particle diffusion time scales is encoded in the low-frequency diffusion tail of the impedance where the response transitions from an approximately 45° Warburg-like slope to a near-vertical line (a feature that typically only becomes apparent at very low frequencies). If impedance data are truncated at higher minimum frequencies (e.g., 100 mHz), this transition is no longer well resolved, and the particle diffusion time scales may become unidentifiable from EIS alone. As a result, the fidelity of diffusion-related parameters is reduced, while other parameters are generally less affected.

Instead, particle diffusion time scales could also be estimated from time domain data (which can also be done in PyBOP), allowing to increase the minimal frequency of the impedance measurements, and hence reducing measurement time.

EIS is also dependent on temperature. Can you give some insight on that?

Yes, EIS is strongly temperature dependent as it affects both reaction kinetics and transport processes in the cell. In this work, all EIS experiments were conducted at steady state in a thermal chamber at 25°C, and the parametrized model was validated at the same temperature, with only small cell temperature deviations observed during the applied drive cycle.

A fully functional parametrized model, however, should be validated over the full state-of-charge range (0–100% SOC) and across a wide temperature window (e.g., −20 to 40°C). In such a case, a thermal model is required, and several electrochemical parameters (most notably the charge-transfer and particle diffusion time scales) must become temperature dependent, for example through Arrhenius-type relations.

This type of temperature-aware model can be implemented in PyBaMM, enabling investigation of the effect of temperature on the impedance. Model parameters could then be estimated from a set of impedance spectra measured across different SOCs and temperatures.

Batteries are inherently nonstationary systems. How was this nonstationary behavior handled and controlled under operating load conditions, as opposed to open-circuit conditions?

Batteries are indeed inherently nonstationary systems. In this work, we parameterized the model using impedance data measured at steady state, i.e., at fixed state-of-charge and temperature after a sufficiently long relaxation period, which allows us to apply the conventional assumption of stationarity.

We recognize that this approach is not practical for batteries deployed in the field, where cells are rarely at steady state when regularly used. In such cases, impedance needs to be measured under operating conditions, for example during charging, discharging, or relaxation. A range of operando impedance measurement techniques exist for this purpose, as discussed in our recent review [1].

Numerical computation of the impedance can still be performed under these operando (nonstationary) conditions, although the procedure used in this work would need to be adapted to account for operating points that are not at steady state. We are currently investigating this extension to enable parametrization of physics-based models from impedance data measured during battery operation, making the approach more applicable in practice!

[1] Hallemans, N., Howey, D., Battistel, A., Saniee, N.F., Scarpioni, F., Wouters, B., La Mantia, F., Hubin, A., Widanage, W. D. and Lataire, J., 2023. “Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy beyond linearity and stationarity—A critical review,” Electrochimica Acta, 466, p.142939.

What work would have to be done for the approach to work for high C-rates?

The first consideration is the choice of model. The SPMe used in this work is a reduced-order approximation of the Doyle-Fuller-Newman (DFN) model. While it is computationally efficient, it may become less accurate at higher C-rates for energy cells (not necessarily for power cells). For certain applications at high C-rates, it could therefore be preferable to use the full DFN model instead.

A second aspect is the type of data used for parametrization. Steady-state EIS primarily provides information around zero current, whereas parametrizing a model for high C-rate operation requires information away from zero current as well. One way to address this is to simultaneously parametrize the model using both time-domain data and impedance data, which is already supported in PyBOP. Alternatively, the model could be parametrized directly from operando impedance measurements (see previous question).

Is PyBaMM & PyBOP a general code that can also handle physics-based models of fuel cells/electrolyzers or are the codes specifically written for particle electrode models for batteries? In principle, the parameters mentioned could be applied to any porous electrode.

PyBaMM and PyBOP were developed primarily for physics-based battery modelling, and most of their built-in models and tools are tailored to particle-based porous electrode descriptions of batteries. That said, at a more general level, the frameworks are built around solving and parametrizing systems of differential—algebraic equations, for example, partial differential equations discretized in space with user-defined geometries. In principle, this means that similar porous electrode models (such as those used for fuel cells or electrolyzers) could be implemented, but these applications are not currently a focus of the libraries and would require additional model development.

Learn more about upcoming ECS Webinars and review previous webinar recordings.

Thanks to the webinar sponsors who make these complimentary programs possible!

|

|

|

Interested in presenting in the ECS Webinar Series? Email your presentation title and abstract to education@electrochem.org for consideration.