Adding a little ultrathin hexagonal boron nitride to ceramics could give them outstanding properties, according to new research.

Adding a little ultrathin hexagonal boron nitride to ceramics could give them outstanding properties, according to new research.

Rouzbeh Shahsavari, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Rice University, suggests the incorporation of ultrathin hBN sheets between layers of calcium-silicates would make an interesting bilayer crystal with multifunctional properties.

These could be suitable for construction and refractory materials and applications in the nuclear industry, oil and gas, aerospace, and other areas that require high-performance composites.

Combining the materials would make a ceramic that’s not only tough and durable but resistant to heat and radiation. By Shahsavari’s calculations, calcium-silicates with inserted layers of two-dimensional hBN could be hardened enough to serve as shielding in nuclear applications like power plants.

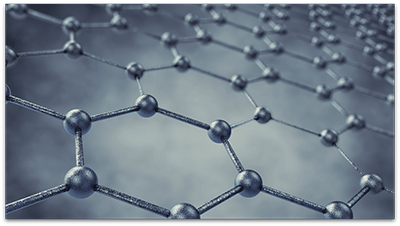

Two-dimensional hBN is nicknamed white graphene and looks like graphene from above, with linked hexagons forming an ultrathin plane. But hBN differs from graphene as it consists of alternating boron and nitrogen, rather than carbon, atoms.

“This work shows the possibility of material reinforcement at the smallest possible dimension, the basal plane of ceramics,” Shahsavari says. “This results in a bilayer crystal where hBN is an integral part of the system as opposed to conventional reinforcing fillers that are loosely connected to the host material.

“Our high-level study shows energetic stability and significant property enhancement owing to the covalent bonding, charge transfer, and orbital mixing between hBN and calcium silicates,” he says.

The form of ceramic the lab studied, known as tobermorite, tends to self-assemble in layers of calcium and oxygen held together by silicate chains as it dries into hardened cement. Shahsavari’s molecular-scale study showed that hBN mixes well with tobermorite, slips into the spaces between the layers as the boron and oxygen atoms bind and buckles the flat hBN sheets.

This accordion-like buckling is due to the chemical affinity and charge transfer between the boron atoms and tobermorite that stabilizes the composite and gives it high strength and toughness, properties that usually trade off against each other in engineered materials, Shahsavari says. The explanation appears to be a two-phase mechanism that takes place when the hBN layers are subjected to strain or stress.

Shahsavari’s models of horizontally stacked tobermorite and tobermorite-hBN showed the composite was three times stronger and about 25 percent stiffer than the plain material. Computational analysis showed why: While the silicate chains in tobermorite failed when forced to rotate along their axes, the hBN sheets relieved the stress by first unbuckling and then stiffening.

When compressed, plain tobermorite displayed a low yield strength (or elastic modulus) of about 10 gigapascals (GPa) with a yield strain (the point at which a material deforms) of 7 percent. The composite displayed yield strength of 25 GPa and strain up to 20 percent.

“A major drawback of ceramics is that they are brittle and shatter upon high stress or strain,” Shahsavari says. “Our strategy overcomes this limitation, providing enhanced ductility and toughness while improving strength properties.

“As a bonus, the thermal and radiation tolerance of the system also increases, rendering multifunctional properties,” he says. “These features are all important to prevent deterioration of ceramics and increase their lifetime, thereby saving energy and maintenance costs.”

When the material was tested from other angles, differences between the pure tobermorite and the composite were less pronounced, but on average, hBN improved significantly the material’s properties.

“Compared with one-dimensional fillers such as conventional fibers or carbon nanotubes, 2D materials like hBN are two-sided, so they have twice the surface area per unit mass,” Shahsavari says. “This is perfect for reinforcement and adhesion to the surrounding matrix.”

He says other 2D materials like molybdenum disulfide, niobium diselenide, and layered double hydroxide may also be suitable for the bottom-up design of high-performance ceramics and other multifunctional composite materials.

The research appears in the journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces.

The National Science Foundation supported the research. The National Institutes of Health and an IBM Shared University Research Award in partnership with Cisco, Qlogic, and Adaptive Computing, as well as Rice’s National Science Foundation-supported DAVinCI supercomputer, supplied supercomputing resources.

This article appeared on Futurity. Read the full article.

Source: Rice University