This Sunday at 2:00 pm ET is ECS OpenCon. We are webcasting it live from the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center in National Harbor, MD.

This Sunday at 2:00 pm ET is ECS OpenCon. We are webcasting it live from the Gaylord National Resort and Convention Center in National Harbor, MD.

Go to the ECS YouTube channel on Sunday to watch.

e are bringing together some of the top advocates in open access and open science to explore what next generation research will look like.

ECS OpenCon is a satellite event of the main OpenCon, an international event hosted by the Right to Research Coalition, a student sponsored organization of SPARC, the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition.

ECS is the first scholarly society to host a satellite event.

Submit your manuscripts to the Journal of The Electrochemical Society

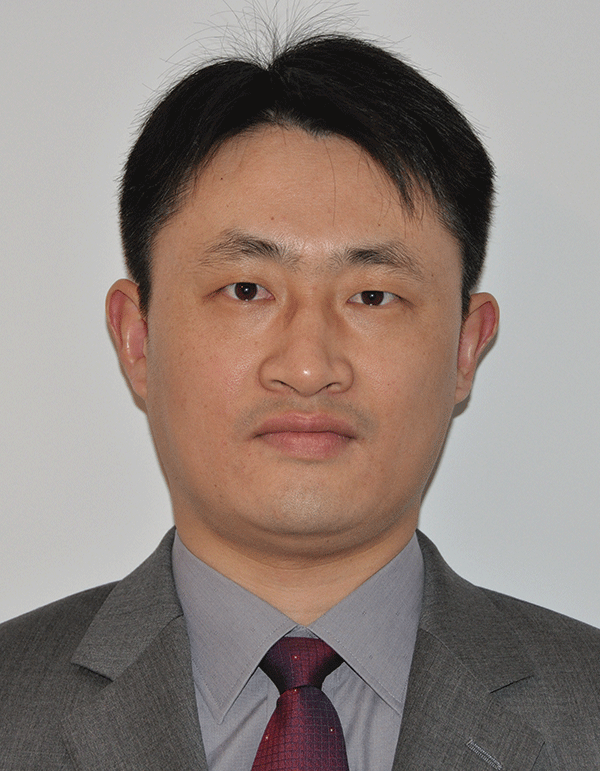

Submit your manuscripts to the Journal of The Electrochemical Society  Minhua Shao is an associate professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, where he leads a research group pursuing work in advanced material and electrochemical energy technologies. Shao’s current work focuses on electrocatalysis, fuel cells, lithium-ion batteries, lithium-air batteries, CO2 reduction, and water splitting. Shao was recently named an associate editor of the

Minhua Shao is an associate professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, where he leads a research group pursuing work in advanced material and electrochemical energy technologies. Shao’s current work focuses on electrocatalysis, fuel cells, lithium-ion batteries, lithium-air batteries, CO2 reduction, and water splitting. Shao was recently named an associate editor of the  Over the summer, librarians and academic leaders in Germany came together to lead a push in taking down the paywalls that block access to so many scientific research articles. The initiative, named

Over the summer, librarians and academic leaders in Germany came together to lead a push in taking down the paywalls that block access to so many scientific research articles. The initiative, named  In addition to the

In addition to the  Nine new issues of

Nine new issues of  A new device has given scientists a nanoscale glimpse of crevice and pitting corrosion as it happens.

A new device has given scientists a nanoscale glimpse of crevice and pitting corrosion as it happens.

A team of engineers from Monash University have successfully test-fired the world’s first 3D printed rocket engine. By utilizing a unique aerospike design, the team, led by ECS fellow

A team of engineers from Monash University have successfully test-fired the world’s first 3D printed rocket engine. By utilizing a unique aerospike design, the team, led by ECS fellow