According to The Conversation, California Governor Jerry Brown has signed a new law committing to make the Golden State the state 100 percent carbon-free by 2045.

According to The Conversation, California Governor Jerry Brown has signed a new law committing to make the Golden State the state 100 percent carbon-free by 2045.

The new law is comprised of multiple targets, committing California to draw half its electricity from renewable sources by 2026, and then to 60 percent by 2030.

California’s mission to stop relying on fossil fuels for energy has been a longtime goal in the making. Since 2010, utility-scale solar and wind electricity in California increased from 3 percent to 18 percent in 2017, exceeding expected targets, due to solar prices drop in recent years. In 2011, Brown signed a law committing the state to derive a third of its energy from renewable sources like wind and solar power by 2020. And in 2017, about 56 percent of the power California generated came from non-carbon emitting sources, placing state over halfway to their goal for 2045.

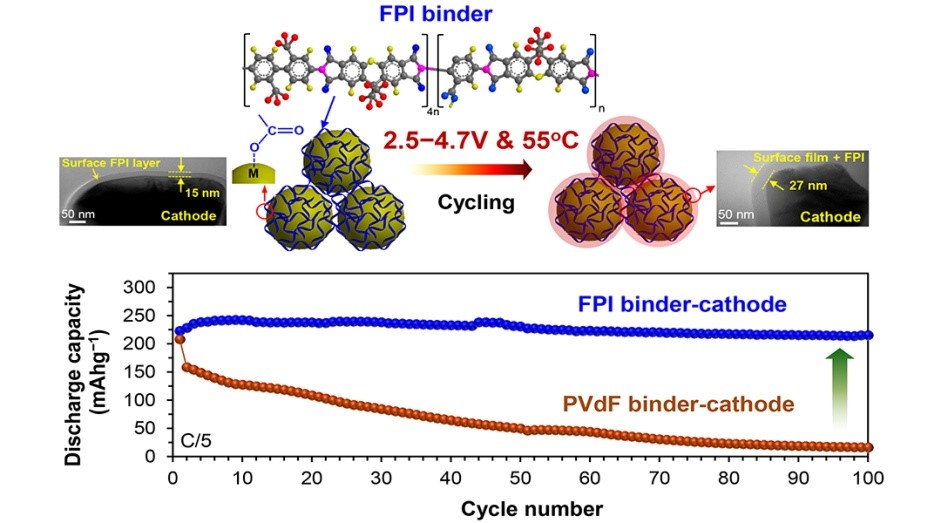

A collaborative team of researchers from Shinshu University in Japan have found a new way to curb some of the potential dangers posed by lithium ion batteries.

A collaborative team of researchers from Shinshu University in Japan have found a new way to curb some of the potential dangers posed by lithium ion batteries.

New research from Sandia National Laboratory is moving toward advancing solid state lithium-ion battery performance in small electronics by identifying major obstacles in how lithium ions flow across battery interfaces.

New research from Sandia National Laboratory is moving toward advancing solid state lithium-ion battery performance in small electronics by identifying major obstacles in how lithium ions flow across battery interfaces.