By: Venkat Subramanian, University of Washington

This article refers to a recently published open access paper in the Journal of The Electrochemical Society, “Direct, Efficient, and Real-Time Simulation of Physics-Based Battery Models for Stand-Alone PV-Battery Microgrids.”

Tesla engineered a good electric car successfully by engineering a car design that can accommodate large battery stacks. Our hypothesis is that the current grid control method, which is a derivative of traditional grid control approaches, cannot utilize batteries efficiently.

Tesla engineered a good electric car successfully by engineering a car design that can accommodate large battery stacks. Our hypothesis is that the current grid control method, which is a derivative of traditional grid control approaches, cannot utilize batteries efficiently.

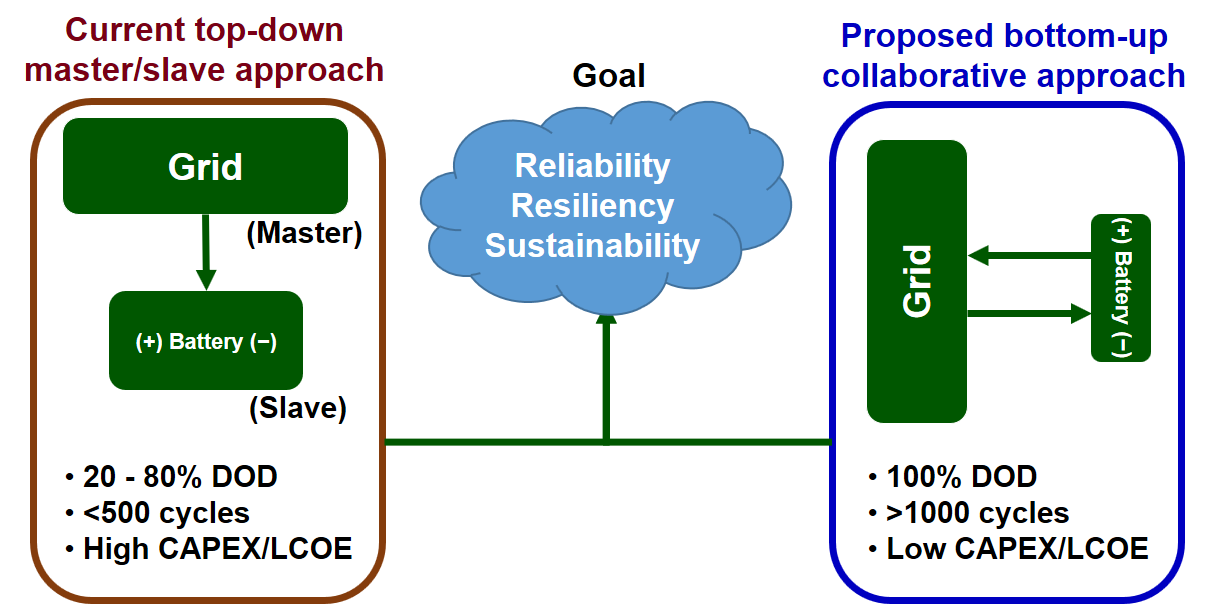

In the current microgrid control, batteries are treated as “slaves” and are typically expected to be available to meet only the power needs. Typically, if grid optimization is done at the higher level, and then batteries are used as slaves, including models that predict fade can be used in a bi-level optimization mode (optimize grid operations and at every point in time, optimize battery operation). This way of optimization will not yield the best possible outcome for batteries.

In a recently published paper, we show that real-time simulation of the entire microgrid is possible in real-time. We wrote down all of the microgrid equations in mathematical form, including photovoltaic (PV) arrays, PV maximum power point tracking (MPPT) controllers, batteries, and power electronics, and then identified an efficient way to solve them simultaneously with battery models. The proposed approach improves the performance of the overall microgrid system, considering the batteries as collaborators on par with the entire microgrid components. It is our hope that this paper will change the current perception among the grid community.

A new paper published in the Journal of The Electrochemical Society, “

A new paper published in the Journal of The Electrochemical Society, “ In an effort to develop an eco-friendly battery, researchers from Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST) have created a battery that can store and produce electricity by using seawater.

In an effort to develop an eco-friendly battery, researchers from Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST) have created a battery that can store and produce electricity by using seawater. A battery made with urea, commonly found in fertilizers and mammal urine, could provide a low-cost way of storing energy produced through solar power or other forms of renewable energy for consumption during off hours.

A battery made with urea, commonly found in fertilizers and mammal urine, could provide a low-cost way of storing energy produced through solar power or other forms of renewable energy for consumption during off hours. Most of today’s batteries are made up of two solid layers, separated by a liquid or gel electrolyte. But some researchers are beginning to move away from that traditional battery in favor of an all-solid-state battery, which some researchers believe could enhance battery energy density and safety. While there are many barriers to overcome when pursing a feasible all-solid-state battery, researchers from MIT believe they are headed in the right direction.

Most of today’s batteries are made up of two solid layers, separated by a liquid or gel electrolyte. But some researchers are beginning to move away from that traditional battery in favor of an all-solid-state battery, which some researchers believe could enhance battery energy density and safety. While there are many barriers to overcome when pursing a feasible all-solid-state battery, researchers from MIT believe they are headed in the right direction. The

The